On Loria Broadly:

The People

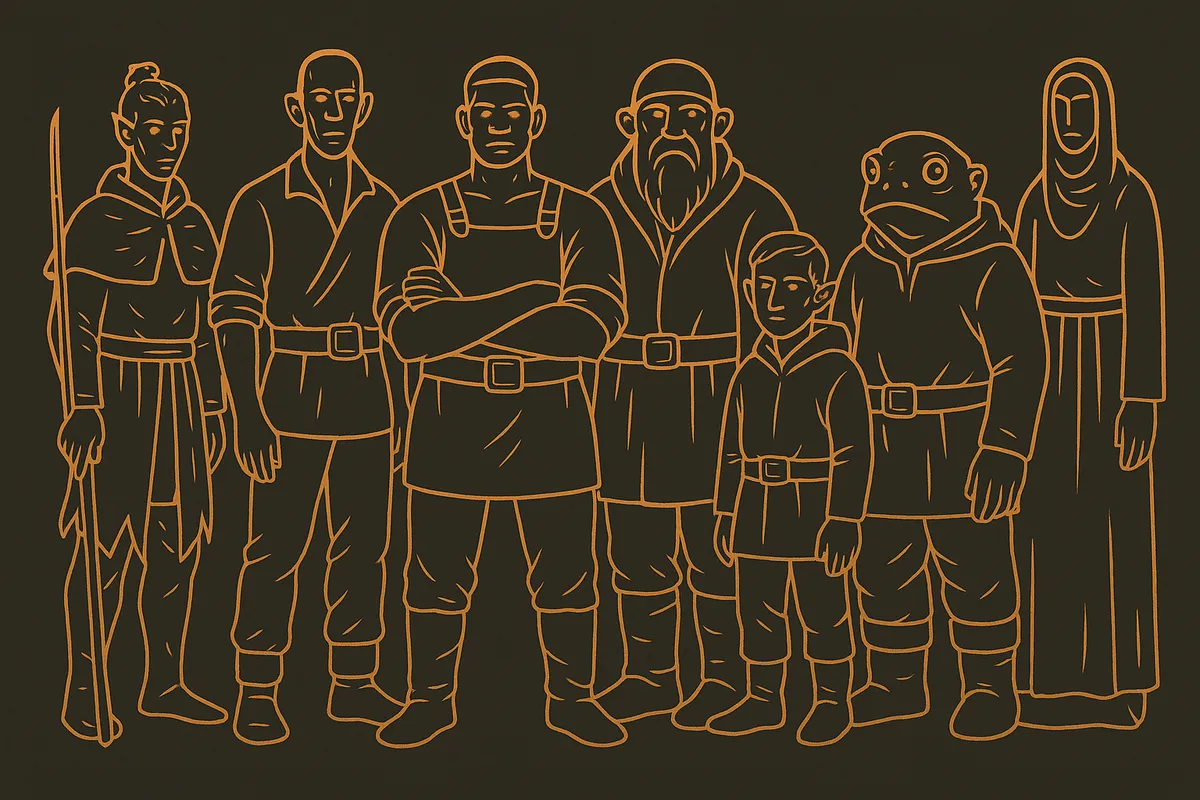

Loria holds dozens of peoples—some thriving, some down to a handful of names. This chapter records eight you are most likely to meet. They are not the whole of Loria’s kin; older lines, hidden clans, and rarer folk will be catalogued in time.

Velmireth (vel-MEER-eth)

Common name: Mireborn

Charcoal-grey to olive-green skin, broad feet with a hint of webbing, and large dark irises are typical. They move quietly and keep their balance on shifting ground. Clothes are oiled against rain; boats are narrow and light.

Origins. The Velmireth are native to the Valemire’s wetlands. Villages stand on living pylons; ropewalks link tree to tree. Their everyday skill is “rot-reading”: knowing which growth heals, which fumes warn, and where footing will hold. Children learn a controlled breath-hold called the shallows-trance, which lets a trained swimmer stay underwater calmly for long stretches.

They greet travelers with food first and talk after. Favors are repaid with repairs—mended lines, reset footbridges, cleared channels.

Ternach (TER-nakh)

Common names: Heightsfolk, Ridgehands

Tall and long-limbed, with weathered complexions ranging from very fair to sun-brown. Rope calluses are common. They stand and move like people used to measuring spans.

Origins. The Ternach make mountains passable. They cut steady stone stairways, throw sky-bridges across ravines, and hang bellframes for wind-carried warnings. A stone face is judged by sound as much as by vein. Crews trust a trained ridge-sense—the practiced feel for sway, tension, and failing weight.

They are strict with their own work. If a span cannot be trusted, they dismantle it and build again. In lowland cities, they still think upward: gantries, cranes, watchwalks.

Veskarn (veh-SKARN)

Common name: Skarners

Deep brown through olive-umber skin; tight-curled hair; forearms dotted with small burn freckles. Many develop tough, supple ember-skin on palms and forearms from years at the forge.

Origins. The Veskarn come from furnace towns and ashlands. Forges run clean; slag is managed and often reclaimed for soil. Their tools are built for honest abuse and easy repair. In a workshop emergency—the spill, the spark, the beam that shifts—they are steady and precise.

A hinge or blade stamped with a Veskarn mark is trusted. Their shrines are simple: a stone, a small thanks left for the creatures that taught them caution.

Havereth (HAV-er-eth)

Common names: Sounders, Saltward

Sun-tawny to deep coastal brown; shoulders thickened by work with line and spar; hair weather-faded from black to rust. Some families show a faint web at the thumb from net craft.

Origins. The Havereth keep the coasts honest. Their harbors are well-kept, tolls posted, and moorings sound. Fog pilots navigate by bell, wake, and smell as much as by chart. Years on the water tune an easy tide-sense—a practiced feel for current and set that catches danger before it shows.

Pride is quiet: safe returns, straight ledgers, and a boat ready for the next crew.

Lierren (LEER-en)

Common names: Brindle, Brindlefolk (outsider usage)

Small—3ʹ10ʺ to 4ʹ8ʺ—usually peach-fair and often freckled; hair flax to chestnut; keen, dusk-adapted eyes. Light steps, sure hands. They tend to carry small measures, picks, and fine-toothed saws.

Origins. Where trees allow it, Lierren grow homes from living wood—platforms, water-balanced lifts, and hidden ropeways. In towns, they keep the quiet machinery working: pumps, lantern pulleys, winches. Apprentices learn line-feel, the knack of hearing faults through the fingertips, and tunnel-breath for tight, careful work.

Far from capital oversight, a shadow trade persists: “narrow-work contracts” that are slavery by ledger. Brindle are targeted most for fungus-farms and seam tunnels—twelve hours on, twelve off, names replaced by tallies. Others are taken too, but small frames and mechanical skill make Brindle profitable. Quiet networks resist: canopy safehouses, night ferries that change flags, and wells with false lids and real rooms below. Seized ledgers are burned; the ash is mixed into the ink that frees the names inside.

Harneth (HAR-neth)

Common name: Dewfolk

Sturdy builds; olive-brown through deep umber skin that freckles and light-warts in damp weather; broad mouths; some lines carry a soft throat fold that gives a resonant burr to speech. Typical height 4ʹ10ʺ–5ʹ6ʺ. Clothing favors waxed leather, layered linen, and river boots.

Origins. The Harneth manage floodfields, river roads, and timber commons. They keep maps of high-water marks and rebuild with those marks in mind. Amphibious skin and steady training let them go bog-still—heart and breath slowed enough to vanish into reeds. Many show a mild tolerance to common green poisons from generations of medicine and diet.

Their praise is plain and practical: “It will hold.”

Ostari (oh-STAR-ee)

Common name: Gloam

Pale, slow to tan; irises dusted ice-blue so noon light halos the pupil; long-fingered hands; a habit of listening before speaking. They are fewer—perhaps a tenth the number of other peoples—and many serve in quiet orders and water courts.

Origins. The Ostari read what lies beneath. Tap-codes and careful breath map caverns and root-roads; bad wells are made good. Their surface workshops sit behind apothecaries and bellfoundries, full of weights and balances delicate enough to “weigh” a heartbeat. Gloam-sight gives them a gentle edge in low light, and long practice makes them very good at hearing strain before it snaps.

If the Underroot hums, an Ostari can often tell you the pitch and the distance by how your teeth feel.

Kassai (KAH-sai)

Common name: none (outsiders sometimes call them Stonebloods, though never to their face)

Stocky—typically 5ʹ0ʺ to 5ʹ5ʺ—with thick shoulders, broad hands, and muscular frames. Their noses are pronounced, ears long and drooping, often weighted with bone or stone piercings. The most striking feature is their skin-marking: a sacred balance of flesh and ink. Exactly seventy-two percent of the face is tattooed in black, leaving twenty-eight bare, the pattern always asymmetrical yet harmonious. Marks spread across the body as life progresses: geometric, fractal, ominous to outsiders but revered within.

Origins. The Kassai inhabit the stone cities of southwestern Loria, building with cyclopean blocks aligned to stars and moons. Their cosmology ties every constellation to cycles of duty, war, and remembrance. From childhood, Kassai are tested by ordeal: hunting beasts, surviving wilderness, proving themselves in contests of strength and will. Each accomplishment is sealed in ink at public ceremony. Tattoos are not decoration but record—of scars earned, wisdom learned, and duties fulfilled.

Warriors train with Spartan rigor. Shamans guide them through visions drawn from myrrhn and starlight, their manipulation of root and resonance among the most feared in Loria. They do not see themselves as conquerors but as stewards of balance—unyielding, unbending, their loyalty to the order of things absolute. Outsiders often mistake their markings for menace; Kassai know them as maps of memory, proof of a life lived in service to both sky and soil.

And many more

Cliff-singers whose pupils hold a fleck of night; salt-islanders who splice rope with their toes; a fae-blooded remnant with elders who count centuries and living names that fit on two hands. Loria is larger than eight entries—these are simply the pages most readers turn first.